Logging on to Strava at the moment is a pretty depressing experience. When I upgraded to a premium account a few months ago, I did so in order to delve head first into the statistics of my running life, to analyse individual runs and to monitor my fitness and progress over time. What I didn't envisage was the prospect of getting injured and being presented with a demoralising daily assessment of my declining fitness.

Friday, October 30, 2020

Strava's depressing truths for all those who are injured

Logging on to Strava at the moment is a pretty depressing experience. When I upgraded to a premium account a few months ago, I did so in order to delve head first into the statistics of my running life, to analyse individual runs and to monitor my fitness and progress over time. What I didn't envisage was the prospect of getting injured and being presented with a demoralising daily assessment of my declining fitness.

Thursday, October 29, 2020

Runners Roundup: Top blogs, sites and social from runners around the world

![]() Next step: Join the conversation in our Facebook Group

Next step: Join the conversation in our Facebook Group

You might also be interested in:

Are you a Clued Up Runner? Submit a guest post today.

Sunday, October 25, 2020

Does anyone really make Runners' World's recipes?

I am a big fan of Runners’ World and, amidst the bills and takeaway menus, it is safe to say that my subscription is the postal highlight of my month. Whether you’re just starting out on your couch to 5K or pace setting for Eliud Kipchoge, RW is a magazine that manages to cater for the masses, offering content that is relatable, useful and eye opening in equal measure.

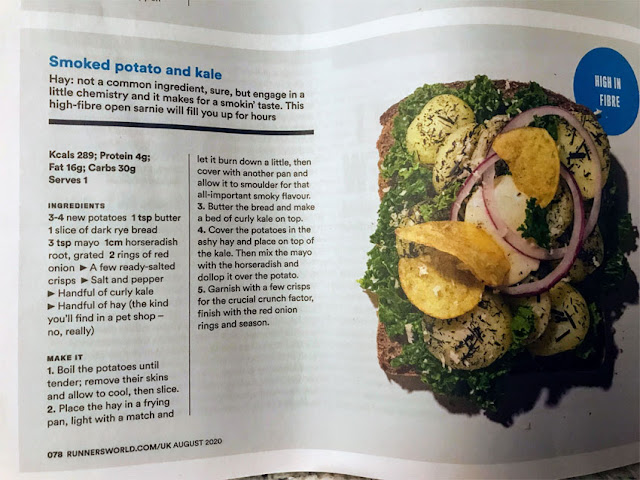

But hold your horses, this is not a puff piece for the country’s leading running title. There is a problem. I have begun to suspect that the RW editorial team is actually involved in an elaborate and long standing game of ingredient dare through one of its regular sections; the recipes.

Of course, I understand the importance of diet when it comes to running and recovery. I appreciate that runners require a certain balance of proteins, carbohydrates, minerals and green things in order to ensure that they perform at their best. But do any of us really need to be eating open sandwiches containing hay (August 2020 issue)?

|

| Hay you, eat this! |

The ingredients being suggested in RW’s regular recipes are bewildering and read like the witches from Macbeth’s shopping list. Granted, occasionally something does catch my eye that is just about within the limits of my culinary skills, but on the majority of occasions, I am left wondering who - other than Jamie Oliver and those red-trouser-wearing folk who do their big shop at a wooden-shacked artisan market - has these ingredients regularly to hand.

Exhibit B: A fig, goji berry and banana smoothie (October 2020 issue). Okay, I admit that my go to smoothie is essentially nothing more than a banana, frozen mixed berries and a block of frozen spinach, but is this morning pick-me-up really worth a trip to Holland&Barret to buy a sprinkling of bee pollen? And who first thought that the one thing they were missing from their smoothie was a hay fever sufferer's worst nightmare?

|

| Un-bee-lievable smoothie |

And then there's the plain hard work, like the celeriac soup with horseradish kefir cream (June 2020 issue). Regardless of the fact that I have just had to Google celeriac (which probably speaks volumes of my spectacularly unrefined palate), the prospect of its combination with cultured, fermented milk (kefir) and grated horseradish root does little to whet my appetite. However, while I am sure the end result is delicious, the coating, drizzling, tossing, chopping, roasting, sauteing, squeezing, blending and baking required to produce my 'gut-friendly midweek dinner,' also seems utterly exhausting. Surely, a can of Heinz tomato is a better mid-week option, and I could spend the time I've saved running instead!

|

| Soup-er hard work |

I am not a foodie, as you can probably guess, and if this post fills up with irate comments from readers who disagree and are happy to make every recipe, presumably from their amply stocked cupboards of pollen and hay, then I will of course humbly withdraw my critique. However, I suspect that I am not alone in the lack of exotic or grass-based food products on my shelves.

If the editorial team at Runners' World, meanwhile, happens to stumble across this post, I apologise if I've exposed your game of random food bingo. However, I also implore you to consider catering for runners whose time is limited and whose tastes aren't quite as exotic, but who nevertheless want to eat healthily and in a way that will benefit their running.

I would welcome more recipes for simple pasta meals, such as an alternative to the humble tuna pasta bake that has become a staple in our household, or simple ways to make chicken a bit more interesting. They don’t need to be intricate and they don’t need to contain ingredients usually reserved for farm yard animals. Simple to cook and delicious to eat. It’s not much to ask is it?

Now, time for a brie and straw sandwich.

You might also be interested in:

Thursday, October 22, 2020

Friday favourites: Social, sites and stuff that's caught our eye this week

Sunday, October 18, 2020

Why not running is harder than running

You might also be interested in:

Are you a Clued Up Runner? Submit a guest post today.

Strava's depressing truths for injured runners

Friday, October 16, 2020

Friday Favourites: Blogs, social and websites that have caught our eye this week

Monday, October 12, 2020

Why running for charity has never been more important

There’s a reason why the London Marathon has raised a billion pounds for charity. Like every other marathon on the planet, the extreme nature of the challenge provides the perfect vehicle through which individuals can raise money for the charities and causes that matter to them. In 2020, however, such mass-participation challenge events have all either been cancelled or postponed and the resulting impact on charities has been devastating. Today, as we face the prospect of a second wave, there’s a very real chance that many charities across the UK will not survive the winter, leaving those who rely on them without the support they need.

Sunday, October 11, 2020

When a nagging Achilles injury rules you out for two months

“No running for six to eight weeks,” said the physio, despite my best attempts to convince him that my nagging Achilles injury wasn’t anything to worry about. Although not unexpected, the news was a blow. I was staring at the prospect of a two month running hiatus and, as I assumed the position for a sports massage of the calf muscle to which my offending Achilles was attached, I tuned out the technical jargon pouring forth from the man to whom I was paying almost a pound a minute, to contemplate the prospect of a prolonged break from running.

What was I going to do instead? What was going to give me the cardiovascular high and the mindful moments that otherwise come from pounding the trails and pavements? How was I going to get through two months of other people’s Strava achievements without becoming irrationally bitter and envious? How was I going to cope with not achieving my 1,000 miles in 2020 goal? What on earth was I going to talk about now? Was I going to have to get on a bike?

Fortunately I was pulled out of my stupor within seconds of the aforementioned physio commencing his massage of my calf. Like taking a cricket ball to the testicles, the searing pain sharpened my focus intently. “Yes, it’s a bit tight isn’t it?” said my torturer as he buried his thumbs into my calf muscle. Every ounce of me wanted to scream; “FUCK YES, GET OFF ME YOU BASTARD,” but I remained face down on the bench and mumbled; “Yes it is a bit, isn’t it,” adopting a typically British approach to adversity by downplaying the excruciauting agony and attempting a conversation.

What seemed like an eternity later, and after the most painful weather-based chat of my life, my assailant completed his thumb battering of my calf and I clambered off the table. A walk around the room didn’t seem to ease the pain, however, as I hobbled around like Bambi on ice trying to encourage my minced calf to recover.

“Might be a little stiff for a while,” said the butcher, before chuckling to himself and relaying further bad news about the Achilles tendinosis that was going to sideline me for the next two months. So, in pain, depressed and £50 worse off, I left the physio with nothing more than instructions to practice weighted heel drops three times a day for the next few weeks.

That was a week ago and today, as I write this, I am most definitely going through running cold turkey. I feel less fit and my mood is generally miserable, but I am trying to cling to the positives brought about by the situation, namely; the fact that I’m saving a fortune on water and shampoo by only showering once a day; the washing machine is taking a break from relentless kit washes and I’m going to get two bonus months of longevity out of my trainers.

The other bonus, of course, is time. I have evenings and mornings back, I have more time with my kids at the weekend and I have the opportunity to finally address the one area of my running that I have purposefully ignored for years; my core strength.

So, while my trainers and trail shoes gather dust, I am on a mission to improve my core strength and mobility. I want to get back to running with a core more iron than rubber, an ability to hold a plank for five minutes and the strength that I know I’m missing to ensure I stay injury free for as long as I can. Of course, I know that I’ve shirked this area of my fitness for far too long, so in a weird way I am grateful to this injury – and to my heavy-handed physio – for giving me the gift of time and the chance to reassess what I want out of running in the long term.

Here’s to plank challenge day one…let’s try one minute for starters!

![]() Next step: Join the conversation in our Facebook Group

Next step: Join the conversation in our Facebook Group

You might also be interested in:

Are you a Clued Up Runner? Submit a guest post today.

Why not running is harder than running

Saturday, October 10, 2020

Cancer, the marathon and my mental health

Two days after Christmas last year I was diagnosed with stage two prostate cancer and, in a little over five months time, I’ll be running the London Marathon for Prostate Cancer UK. The latter, however, is not the only surprisingly good thing to have come out of the former, cancer has given me a renewed enthusiasm for running and a far greater appreciation of the role physical activity can play in tackling anxiety. Granted, it’s also robbed me of my core strength and confined me to the sofa at times, but today - as I embark on training for my first ever marathon - I find myself oddly grateful to it for giving me the opportunity to fulfil a lifelong dream.

I am now 41 and have been running since my mid-twenties, routinely undertaking 5KM for fun, challenging myself to the occasional 10KM race and chalking up a single half-marathon. I am also addicted to Strava, have two pairs of running trainers and am partial to the occasional banana. I feel like a runner, albeit one who has a long way to go until he’s anywhere close to being ready for a marathon.

Prostate cancer, however, came out of nowhere. I was 30 years below the average age for those newly diagnosed - I have no family history, I’m not black and I had no symptoms. I was, in fact, the 10,000-to-one rank outsider unlucky enough to contract the disease aged 40. But far from being unlucky, I was actually extremely lucky. My cancer was picked up at a free NHS health check to which I had been invited upon entering my fourth decade. My routine blood test flagged a raised PSA (prostate specific antigen) level and six-months of further tests later, I was diagnosed with a tumour that, thankfully, was confined to my prostate. Had I not attended that health check - and 60% of those invited don’t bother - I was told that my cancer would have been incurable by 45 and I would have been dead by 50.

These are sobering words to hear and although I can now see how lucky I was to have had it caught early, the months between that first blood test and diagnosis were dark. I am married to an incredibly supportive wife and have two young children. However, I felt numbed by the prospect that this thing inside me could take this all away from me, and me away from them. It felt grossly unfair and the prospect of surgery, coupled with talk of life changing side effects, terrified me to the core. What was my life going to be like after all of this? This was something that 70-year-old men have to cope with, not me, not in my 40s.

My mind wouldn’t let me escape this fear either. Everywhere I looked I saw adverts for cancer charities and, if it wasn’t heartstring-pulling videos of patients and relatives, I was struck by bouts of jealousy whenever I would see other men my age running, walking, talking, cycling and basically doing anything. They didn’t have what I did and, as they gleefully went about life it felt to me like they - and their fully-functioning prostates - were mocking me. My head was a mess. At times, when distracted, I was almost functioning as normal, but at other times I would find myself on the verge of tears, unable to concentrate on anything and wanting to do nothing more than sleep to escape it. Much to my wife’s frustration I also didn’t want to talk about it. I certainly didn’t want anyone to tell me that they were sure it was all going to be ok, nor did I want anyone to remind me of how lucky I was to have caught it early. In my book, it wasn’t good to talk.

However, it was good to run.

Prior to the surgery I would have to undergo to rid me of the offending gland, I was determined to ensure that I was as fit as I could be. Running was therefore both a means to potentially minimising my recovery, and to escaping my own mind. I became a bit obsessed, increasing the time and distance in the weeks before I went under the knife and rerunning the same routes over and over again, driven by a desire to improve my average pace and secure an upward curve on my ‘matched runs’ graph. It was a cleansing experience, allowing me to focus on nothing more than my breathing and my pace, taking in the canal as I ran along the towpath, losing myself in Coldplay and Snow Patrol and glancing perpetually at my watch every time it buzzed to let me know another kilometre had passed.

By the time I was due to head to the hospital I was ironically fitter than I had been in years. I felt physically fantastic but, with my Strava trophy cabinet bursting with PBs, I once again found myself battling the unanswerable question; why was this happening to me?

Fast forward two months. My surgery went well, as did my physical recovery, despite a large percentage of my waking days being spent either in front of Netflix or plugged into the PS4. I healed quickly and was soon able to walk around, increasing the amount of time I spent on my feet each day and building up my stamina and strength. The worry was still there - I had the prospect of the pathology report on my prostate to come and the blurred images of an uncertain future in regards to elements of my life in the long term - but focusing on my physical recovery helped to take my mind away from these unknowns.

Seven weeks after surgery the nurses gave me the green light to attempt a run. My insides had healed enough to handle the impact of feet on pavement, so as long as I didn’t beast myself or start lifting serious weights, I was good to go. It was music to my ears.

Strapping on my trainers, mentally contemplating a route, choosing a playlist on my phone and locking on to a GPS-signal felt like I was on my way back to normality. This was ‘F*ck You Cancer: Run 1’ on my Strava profile and every step of the 3.9KM felt like I was casting off the blood tests, the hospital gowns, the catheter, the pills, the needles and all the other paraphernalia that had become my life for the past two months. This was a freedom that I had taken for granted before and was now the unprescribed drug that was going to get me back to myself. I knew from that first run that I was going to get out as much as I could and use the analytics in Strava to track my progress as I went.

FYC: Run 2 followed a couple of days later when I returned to work, I stretched it to 5KM and I shaved 20 seconds off my average pace. This continued over the coming days and weeks, helping me to regain my fitness and providing the perfect distraction from thoughts of follow-up tests and hospital visits. I felt stronger in myself, more able to talk about all that had happened over the previous six months and more in control of my anxiety. My body and mind also felt like they were helping each other out and the ability to visually see my average pace figures gradually climbing back up the ‘matched runs’ graph, towards my pre-surgery times, was hugely encouraging.

The benefits of physical activity in regards to mental health are well documented and proven. Indeed, I work for a charity that combines the two in its approach to supporting fire and rescue service personnel and I have seen firsthand how powerful it can be in helping those dealing with tremendous psychological trauma. However, actually realising it after reading and writing about it from a distance for so long is somewhat of an epiphany moment. The act of pushing your body to do more and go further clearly has as powerful an impact on one’s psychological wellbeing as it does on one’s physical health. It delivers a high that no man-made chemical or intoxicant can and clears the crippling fug that can descend and grip you when anxiety takes control of your rational mind.

As someone who hates taking pills and the concept of ingesting anything artificial to alter one’s mood, running strikes me as mother nature’s gift to us all. It is free, it requires no membership or fancy equipment, no prescription and no one else. It is a pastime that brings nothing but benefits to the human body and, as I pass the FYC70 milestone en route to the start line in Blackheath on 28 April, I continue to meet fellow first-time marathoners and cancer survivors - via the medium of social media - who share my view.

Cancer is the darkest and most terrifying word many of us will hear in our lifetime, but the fear - while all too real - is nothing more than our mind’s way of processing the concept of our own mortality. Running is the perfect means by which to escape it. It worked for me, and I’m convinced it will work for you.

See you for FYC London Marathon next year.

![]() Next step: Join the conversation in our Facebook Group

Next step: Join the conversation in our Facebook Group

Sunday, October 4, 2020

Runinng with a cold during the coronavirus pandemic - snot easy!

For all this and a whole lot more...

Join the Clued Up Runners Facebook Group

Having spent a fair bit of time trawling Facebook of late, I've found that most of the running-related groups on Zuckerberg's mother...

Popular posts right now...

-

As I trudge along the towpath, breathing heavily and sweating like I have a tap on my forehead, a runner passes me in the opposite direction...

-

Sam Mendes' epic film 1917 told the story of two soldiers charged with delivering a vital message to the front line. At a time when comm...

-

Whether you're a seasoned runner, a marathon regular, a trail running addict or a newbie, we all have days when we just can't be bot...